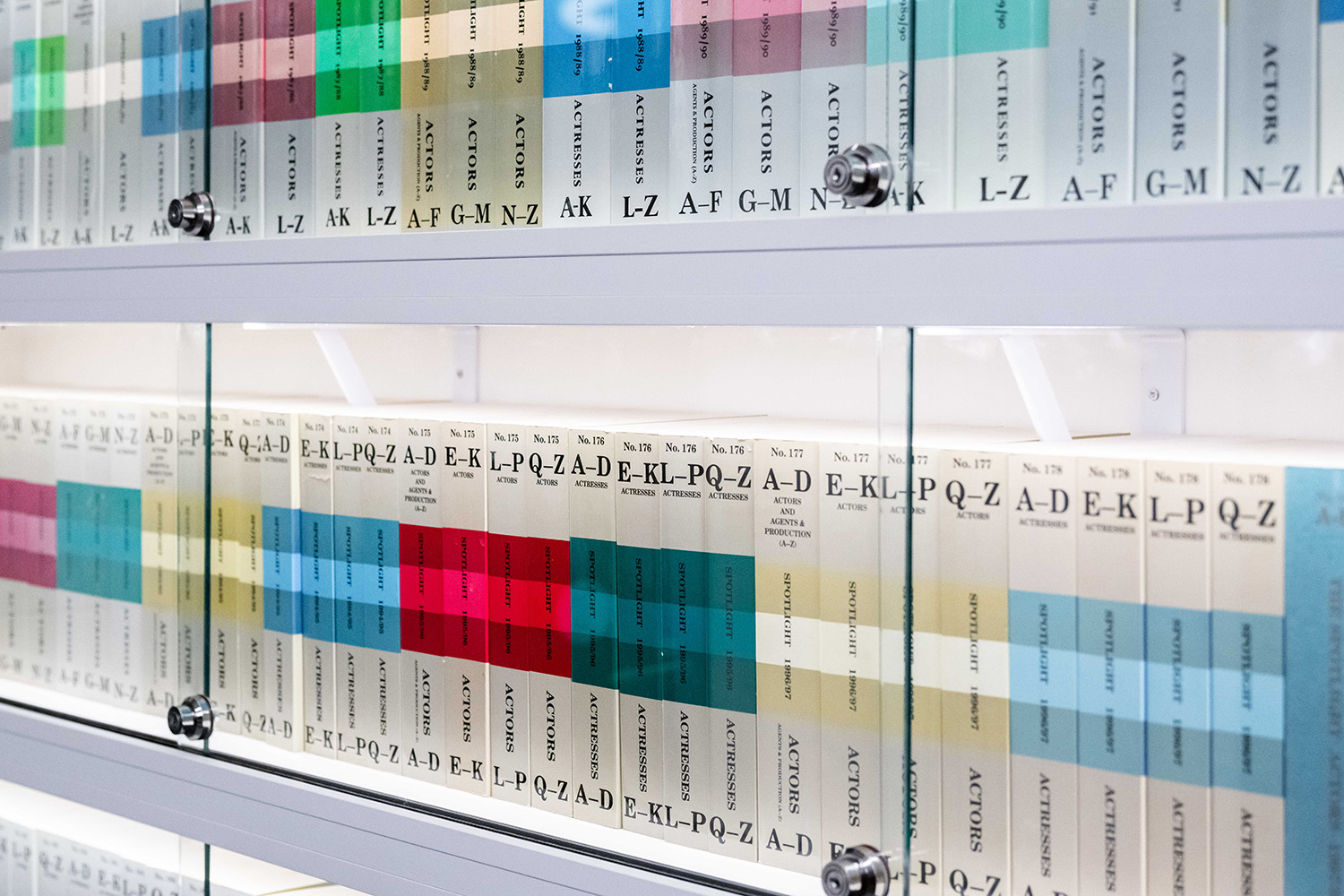

Everything a performer needs to know about taxation, worker rights and contracts.

In this episode of The Spotlight Podcast, you’ll find out all about your rights and duties as a freelance worker. We talk Alan Lean and Stephen Duncan-Rice from Equity, who give us the lowdown on everything a self-employed performer needs to navigate the less than fun, but super important legal stuff on the job. This includes all the essentials you should know about working rights in the UK, taxation, contracts, and much more.

37 minute listen.

All episodes of the Spotlight Podcast.

Episode Transcript

Christina Care: Hello and welcome to this episode of The Spotlight Podcast. My name is Christina Care, I work at Spotlight and today we’ve got a very juicy topic for you. It is tax and contracts. I know, I know, not the sexiest topic ever, but really important for all freelance workers.

We’re talking today to Alan Lean, who is the Tax and Welfare Rights Officer at Equity and Stephen Duncan-Rice who is a recruitment organiser at Equity. Alan and Stephen answer a lot of really important questions about tax, welfare, contracts, things to do with pay, negotiation, your relationship with your agent, and the kinds of questions you should ask them. Basically everything you should be aware of to make sure that you work happily and get paid the right amount.

Thank you to everybody who sent us their questions via social media. Keep in mind that we’ll be asking for your questions on social media in future. For now, take a listen.

Alan, Stephen, thank you so much for joining me on The Spotlight Podcast.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: No worries.

Christina Care: You both held a session recently with Spotlight as part of our Open House on knowing your rights, on freelance life, and on taxation. Can you tell us a little bit first, well, Stephen, I’ll start with you. When you talk about knowing your rights, what are you alluding to? What does that actually mean?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It’s basically about protecting yourself when you’re working and ensuring that you’re being treated properly. I mean, everything that Equity does is really just trying to ensure that you will have a decent, good experience at work. And that often comes down to money, but it surrounds everything else about your working life. And so that’s really what we focus on.

So, it covers everything, basically, from the auditions process – although we’re less involved in that as a trade union – it’s about when you’re employed when you’re at work. But it’s about everything to do with the quality of your working life if that makes sense.

Christina Care: Right. It does make sense. And obviously, a lot of that starts with the contract. So this is not a subject I think our members often like to talk about, but it’s quite important that they have a contract and that it’s a good contract. What does a good contract look like?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: You should be able to see it.

Christina Care: Yeah. So it should be visible and given to you in writing.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It is your right to see your contract. And unfortunately, in the entertainment industry, particularly in the UK and that’s part of the industry I’m more familiar with, seeing your contract is not always a given, particularly television, film. It can be very late in the day before you actually see a contract. And particularly, even in live performance, and my speciality is really live performance, that’s where I work predominantly, people will only be aware of a deal memo. They might not see all the facts or particulars of their terms and conditions.

And the danger is, if you’re going to work and you have not seen a contract, you’re not clear about all the explicit terms and conditions of your employment, by doing the work, you are accepting those terms, even if you don’t know what those terms are. When I do a workplace visit, I will always ask the people there, have you seen your contract? And sometimes it’s yes, sometimes it’s no, sometimes it’s with my agent, all that. So being able to see and understand your terms and conditions is the most important thing. And then maybe you can evaluate whether it’s a good contract or not.

Christina Care: Right. And you’ve just mentioned agents there, which is interesting. I think a lot of people who have representation assume therefore that it’s in hand and it’s taken care of. Is that a good method? Should people be more aware or just leave it to their agents?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Don’t leave it to your agents. The agent is there to find work for you, they’re there to negotiate the best possible terms for you in the market, that’s what they do. They get paid when you get paid. But they are working for you. They’re doing a job for you and if you’re an adult, you need to be aware of your terms and conditions of employment. This is your money we’re talking about.

Christina Care: Yeah, for sure.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It’s your money. You’re earning a living, you’re a professional. So it’s your responsibility to be aware of what you’re doing and what is being expected of you. So I would always insist that you have a copy of your contract because you might move agents at some point, and those contracts may have a life beyond the work itself. So, for example, particularly recorded media, royalties, residual money, secondary payments – particularly in an environment where there are lots of pre-purchase buyouts essentially – is in place. You want to understand what the limitations of that are.

There’s a lot to it. So get eyes on your contract, keep copies for yourself, respect your agent, but understand as well that you should have access to that information and don’t just leave it to someone else.

Christina Care: Yeah. You should be aware of all of that stuff. I want to get to a fairly tricky topic with you now, which is to do with pay. Can either of you shed much light on what people should be asking for or how can they really negotiate anything on that front? What is the expectation? What’s a realistic expectation?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Oh, well, that’s a huge question. The union negotiates minimum rates of pay under the umbrella of collective bargaining. That’s not something that is widely understood and sometimes the Equity minimum is confused with the Equity rate. There isn’t an equity rate, we negotiate a minimum under the framework of collective bargaining when we have union recognition with certain employers. So there are Equity contracts and there are non-Equity contracts, and the number of Equity minimum rates are colossal. There are loads of them. So I would always encourage anyone who’s not sure if they’ve been offered a fair deal to contact us and we can let you know what the minimum is in that particular area. I don’t know if you’ve got anything more to add.

Alan Lean: Not really, no, but I mean, members can go on the website, can’t they, and have a look at the agreements?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: They can. Yeah.

Alan Lean: And the minimum rates on the website.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: I just tried that out actually last week, because I was doing a visit to a commercial tour and I couldn’t remember what the minimum rate was for one of the West End theatre venues, one of the categories. And I was able to go on the website and it actually does break it down quite nicely. So if you’re registered with the Equity website, you’re a member and you get your little password, you go in, you can check the rates. And the new website is actually pretty good for doing that. It’s got a nice, clear breakdown of those minimums, but there are loads of them.

Always interrogate what is being offered. Often now people work under a buyout agreement. So certain duty to bring pre-purchase, particularly in theatre we’re seeing this, it’s de facto the norm in some of the sectors of the industry, particularly advertising, commercials, but understanding what you’re giving away for the pay that you’re receiving. So if you’re getting £800 per week in theatre, is that just what they’re paying you? That’s your basic weekly wage? Or is it pre-purchasing overtime, travel, working on Sundays, public holiday work? What is coming with that? And actually, it’s really important for you to be able to interrogate that figure to be able to determine your own value and how the producer’s valuing you as well because it makes it really difficult for our members to be able to assess sometimes.

Christina Care: Of course.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It’s a really big question.

Alan Lean: And just to add, I mean, it’s not my area so much, but we’re always trying to extend the areas which are covered by collective bargaining and minimum rates. So there’s the ITC agreement, isn’t there? And the Fringe, the whole Fringe theatre area, which is getting more and more in line with standard minimum rates, which is a great thing.

Christina Care: Yes, for sure. And I mean, it’s a very complex subject, obviously, as you said, a big question, I know. But I guess part of the difficulty is obviously the nature of the work, in that you are potentially negotiating contracts all the time or negotiating pay all the time and you’re getting paid in dribs and drabs it could be. You might have one job here and another job there and so there are multiple sources of income.

Alan, in terms of actually getting set up and keeping track of that income, what do you advise to people when they’ve got to later down the track actually file a tax report?

Alan Lean: Well, I think the important thing is record-keeping, isn’t it? And we go into some detail on this in our tax guide, which we give to members. You have to keep records for the tax year, you have a final filing date after the tax year, which is the following January if you’re doing it online. So you have to keep records for five years and 10 months from the last filing date. So, unfortunately, we still haven’t moved on to digital systems. So, that still means people filing things in hard copy if they can. If you haven’t got actual receipts, you can go by the evidence of your bank statements or PayPal, but that’s a key element, keep a very close record on money coming in, what was it? Money going out, what was it? So that you have a handle on that.

Christina Care: Does it change in terms of, now there’s quarterly submitting coming into play? Do you advise people to set things up differently?

Alan Lean: The quarterly submitting’s not actually going to come in for income tax. That was what they were trying to get to with making tax digital, but that’s been shelved. We actually lobbied very hard on that with others, for that to be shelved. It was put back to 2020, now it’s been put back to beyond that.

Quarterly is in for people registered for VAT, if they’re above the VAT threshold, but the same principles apply with that. You just keep a very careful record of your expenditure and income and you claim the expenses which you’re able to claim. In my experience members under claim expenses.

Christina Care: Right. Well, that is a very common question, I think, that comes in is, what can I claim? The number one thing I wanted to ask about that really was to do with your membership and whether or not you can claim that. So your Spotlight membership, your Equity membership?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: We’re nodding.

Christina Care: You’re nodding.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Enthusiastically.

Alan Lean: They’re all allowable. A slight misconception is what they do, is they reduce your taxable income, all those things. So when you’re doing your tax return, you’re putting them in against your turnover and that’s reducing your net taxable income. You’re not in any sense getting a refund of that money as sometimes members think. But certainly Spotlight, yeah, and Equity membership. What are the others? IMDB, that kind of thing. There are others, as long as they’re wholly and exclusively for business purposes. There are some expenses which are dual purpose. That’s always a bone of contention with HMRC.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah, I mean, gym membership. I mean, imagine if you’re doing Magic Mike the musical, you could probably maybe argue for a portion of that.

Alan Lean: Well, one thing I’d mention with gym membership – sorry I’m talking away from the microphone – one thing I mention with gym membership is that HMRC has got a much harder line on that in the last few years.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Oh, really?

Alan Lean: So really what we’re saying now is, claim it if what you’re doing is very physical. So say you’re a dancer or a stunt performer, or you’re in a very physical role, claim a pro-rata amount of it for the period that you’re in it. There’s a lot of variation in what accountants are putting throughout there. Some are still putting it through, some are putting through a proportion. I think we’re taking a cautious line on it.

Christina Care: On that. Yeah. What about things like costumes?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Clothes are always a problem.

Christina Care: Yeah.

Alan Lean: Clothes are always problematic. Costumes are fine if they are used for performance work. If it’s clothing that you could wear every day and HMRC was to inquire into your tax return, they’d probably disallow it because of a court case that went on and on for years with a barrister. So, they found, the Supreme Court, basically her court clothes were disallowed on the grounds that she could have worn them every day. So you have a problem once it’s everyday clothing. With things like audition wardrobes, you can argue that those are the things you’re only ever going to use for auditions and not for any other purpose. But generally speaking, as Steve rightly says, clothes are problematic. Don’t ever claim. And get advice.

Christina Care: Right. Okay.

Alan Lean: Can I just say though, because you might not ask this, if you’re going to get an accountant, we have a list for members, there are all sorts of reasons now why it’s really important it’s an accountant who knows how the entertainment sector operates.

Christina Care: That was literally going to be my next question – what’s the value of having an accountant? Do you need one?

Alan Lean: You really do need one who knows the sector, particularly because as we know from recent events, HMRC are getting ever more interested in our sector and there are issues around their approach. And so you need someone who knows how our sector operates. People work abroad a lot. So you’ve got all those sorts of tax implications when you go abroad, tax is held from your earnings. So it has to be someone who’s clued up, basically, with how the sector works.

Christina Care: Right. You’ve mentioned there’s a list, but are there other general things that you should look for that would make for a qualified accountant?

Alan Lean: Well, they belong to one of the recognised accountancy bodies, chartered institutes. There are three or four different recognised bodies where you would be…

Christina Care: So as long as they’re part of one of those and potentially have some experience in the sector?

Alan Lean: Yeah.

Christina Care: That’s a good starting point.

Alan Lean: It’s a good starting point. I’d be careful about accountants… choosing your accountant that is, not accountants generally! That’s not something we want to put out there as a quote [laughs]. But choose them carefully and even if you pay an extra £200 a year, it’s worth it if you get someone who can maximise, for example, your expense claim. That sort of thing.

Christina Care: Right. Yeah. So it can be very worthwhile?

Alan Lean: Yeah.

Christina Care: I want to go back to the contracts side of things for a second and ask you what the common sort of pitfalls are and the common errors that people overlook or potentially just forget about? Because obviously the minimum definition of a working contract is not really the same thing as what you would ideally want.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. I mean, people sometimes don’t understand that if they haven’t seen something in writing or if they haven’t signed anything, that there’s no contract in place. But in UK law, a verbal agreement can be a contract. It’s just if you then wanted a third party to adjudicate or come to some kind of decision if there’s a dispute, then it’s really hard in those circumstances. But generally it’s, if you know when you’re doing something, what you’re doing, who’s engaging you to do it, what you’re getting paid, that’s kind of basic details, then essentially you have a contract in place.

There is a lot of misperception that if you are on a non-union contract, that the union is not able to help you or would not be willing to help you, that couldn’t be further from the truth. You are more likely to need help if you’re on a non-union contract, because in my experience in live performance – and we’re very lucky, we have quite broad coverage of union agreements – but there are in the commercial sector some producers who elect not to use Equity agreements, but when we see those, they’re very often very poorly written, or they’re very one-sided, they’re partisan agreements, they’re written purely in the interests of the employer. They’re not really that concerned about the perspective of the worker.

And sometimes, and we often notice that they are in breach of legislation at times. So it might be in regards to holiday pay, which is a regular issue, that holiday pay is not being calculated at all, or if it is being calculated, it’s not being done properly. And these things are statutory entitlements to workers and our members, and if you’re an actor, in most cases, you’re going to be categorised as a worker under UK legislation, and therefore entitled to some basic statutory rights, which include national minimum wage, holiday pay, and the European Working Time Directive while it lasts. So these are often things that are neglected or overlooked in a sector that has some worrying lapses in professionalism, I would suggest, from producers. Sometimes it’s out of ignorance, sometimes it’s out of wilful ignorance. And many of the people listening to this will probably have worked on non-union agreements. They are more than able to come to us if you have any questions at all, you can put a contract to us. Anything you submit to us is always confidential, we will not disclose any information to any third party. We’ll give you an overview and then let you decide what you want to do, if you wish to accept the work, then you’ll go into it with your eyes open. If you’re in the work already and there’s a disagreement, some kind of dispute, we can still represent you as a member. So that’s often a misperception.

Christina Care: Yeah. That’s really good to know that people can still ask the question at least.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Absolutely. And you are more likely to need help quite frankly.

Christina Care: Yes, of course. I want to ask you about a slightly more unknown area of work, which is around the internet. It is an increasingly common thing we notice at Spotlight that we’re getting more and more breakdowns for work that would appear on YouTube or some other sort of online platform. And those areas seem to be less legislated and less well understood. Do you have any advice, particularly, well in either respect, contracts or taxation? How can you manage that work better?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It is in the interest of the worker who’s being engaged on such a contract to restrict the usage where possible of their work. The idea being that you can extract as much money as possible from the licence of your work. So it’s very important for any artist who’s being engaged for work on the internet, or they know that their work is being filmed and then may be used in different ways that they have an understanding of where it’s going to be used, how often? In what regions? Is it going to be global? And then to assess the value of that work.

And it’s very often, it’s a challenge that has faced actors performing in adverts and commercials for decades now, trying to understand the value of their work and to be able to negotiate a fair rate for that work without really knowing, maybe almost having to gamble on whether or not an advertising campaign will be successful. And again, with the internet, you don’t know. Something could just… I mean, it’s an ocean and your work will be less than a drip of water in that ocean. Or it could be more than that, but even so, how do you calculate the value of that?

That’s why agents are useful, but it’s why seeing contracts are useful, but just go back to my initial point, your priority should be trying to extract as much money as possible from the work and that means understanding how the work is going to be used, where it’s going to be used, how long it’s going to be used, be wary of things like ‘in perpetuity’ or those kinds of terms.

That means that if you’ve got some kind of restriction on it, it means if it’s successful, they have to come back to you and renegotiate an additional fee for your work. And where possible, you should try and do that as best you can, even though market forces are very often against you. And that’s because we have an issue, and it’s not just for the UK, it’s a global thing, but there is a surplus of labour and not enough jobs to accommodate that labour. So, the physics are against you.

Christina Care: Yeah, for sure. I mean, it’s so hard to quantify because if you’re getting paid per view on a YouTube channel or something like that, that’s-

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. It’s being able to calculate that though. So is the person paying you the money? Are they able to provide a record of how many? Can they examine? Is there transparency? Who is keeping a track of the views? Is there a third party doing it? Are they doing it? Is anyone doing it?

Christina Care: Right. Yeah.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: And we have, there are union agreements in place to govern things such as iPlayer, Netflix, services of that ilk. We have collective licences with these outlets and we are able to examine, to forensically analyse what’s being seen, when it’s being seen, and to gauge that and distribute monies from that, which is incredibly valuable use of a union. That’s just one of the things we have to do.

But very often people accept agreements without any detail of knowing, how are you going to bill? I mean, it’s one of the issues of buyouts or deferred payments on films, how is anyone going to be on licence for the accounts? Is anyone keeping accounts of this work? How is it being done? Is there an objective third party looking at this and then being able to distribute the information fairly? Or is it all coming through the producer? You’re having to take the word of someone.

Christina Care: Yeah. Right. Of one person.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. A lot to unpack.

Christina Care: Yes. A lot. That kind of leads me to another question, which is about if you’re getting paid for work in another territory, in another country. And particularly, we’ve had a question asking about working in Europe. So in terms of doing your taxes at the end of the year, what are you doing with that work if you’re getting paid in another place?

Alan Lean: Well, as things stand, what you have is a series of double taxation treaties between European countries and the UK, many of which have been in place for many years. Now, for historical reasons, entertainers and sportsmen – I think it still says sports men – treaties, are in a special category where if they go and work in a European country, it’s the place of work, which is important. So they’ll be subject to withholding tax at different rates according to which country you go to. And what you can do is offset that against your UK tax liability. We do go into some more detail in the guide about how to do that. So basically, if your taxed at, I don’t know, 25% in Italy for the performance work you’ve done in Italy, then you offset that against your basic rate tax here. There may be some tax you can’t offset because of the different tax rates. So there are other options that you can follow there, including trying to get a refund. That’s quite complicated.

Christina Care: I see. Right.

Alan Lean: Essentially you do, our members are often surprised, but you do get subjected to withholding tax when you work abroad, just as those coming here will be subject to our UK withholding tax. I think originally, it has something to do with people like The Beatles going abroad, making huge sums of money on foreign tours, and the country in question not getting much taxation revenue out of it.

Christina Care: I see.

Alan Lean: It does come back a bit to my original comment about the accountant, because when you’re trying to juggle the best option for dealing with foreign tax incurred, you need a good accountant who knows the sector. The other thing is keeping track of your expenses when you’re abroad, because you may well be able to include those in your tax return, converted into Sterling. It’s a difficult area, foreign taxation, there are multiple, multiple different regimes.

Christina Care: But it’s good to know, particularly the keeping note of your expenses point there.

Alan Lean: Yeah. And the answer is you can do something about it. You can offset a lot of it against UK tax.

Christina Care: That’s very interesting. I want to ask you both about younger performers, if possible. We’ve had a question from someone who is 14 on Instagram who wanted to know what the value of getting an Equity card would be if she needs one as a 14 year old performer. What could you say to that?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Well for me, essentially, it’s no different from an adult. I mean, in terms of, if you’re working regularly at 14, and we do have many people working regularly under what would be considered an adult age, you want to make sure that you’re looked after and being treated well wherever you’re working.

Christina Care: Yeah. In the same way.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. So it’s no different really and they’re able to join Equity from the age of 10 upwards actually.

Christina Care: Okay. Good.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: So, we have a Young Members Committee. Our membership as an average is quite young, for a trade union at least. So I’d say, yeah, it needs to suit you. So if you are working regularly, then I encourage it. If it’s only intermittent work and you’re actually planning to go and study, so you plan to go to drama school, you might want to consider our student membership scheme and then gradually go up through that pathway. So student membership, graduate membership, full membership, as opposed to joining as a full member.

Because once you’ve become a full member, you can’t go back to be a student member, even if you’re 14, you’re working regularly in film, TV, whatever, and then suddenly you go and study at drama school, you can’t then become a student member. So, consider the pathway you’re on at the moment, but it’s whatever’s going to work best for you. Paying your subscriptions, it costs money to be a member of Equity. So is that going to work for you?

Christina Care: Right. But I think there’s another sort of question there implicit about parents, because often it’s the parents who receive payment, particularly on behalf of younger kids. What advice can you give around that in terms of protecting the performer?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Well, you want to protect your child from exploitation. If your child is working regularly, then you want to make sure they have access to, or that you have access, to representation if there is some kind of problem at work. I advise anyone who’s putting their child into a workplace that they’re fully conversant, not only with the contract, but also with the rights of their child. Local authorities are very often the key to that. And local authorities have different work patterns.

Christina Care: Yeah, they do.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Different processes depending on where you are. So I would just encourage, I mean, you want to protect your child. Yeah. Or I hope you do.

Christina Care: In terms of actually doing taxes, are you submitting tax reports for babies?

Alan Lean: You still are. Yeah. No. I mean, they’re still subject to income tax, even young children. So what tends to happen is the parent or parents act as agents for that in terms of filing the return. But the same considerations apply in terms of getting tax advice and all the rest of it. I’m afraid the revenue don’t mind this, they’re going to get their taxes off you even if you’re a baby.

Christina Care: Right. They’re still coming to collect.

Alan Lean: They’re still coming after you.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. If you’re some 13 year old working in Harry Potter, there’s probably quite a lot of revenue to collect.

Alan Lean: Depends on your level of earnings of course, even so. They’re still interested.

Christina Care: Right. I’ve got another interesting sort of parent-related question here. Someone’s asked us, if your parents support you, do you have to put that on your tax report? So I assume they mean by that getting sort of a ‘gift’ of money from their parents. Should you put that on your report?

Alan Lean: Well, again, you’d need to know the details on any individual case. If it’s a bona fide gift, it’s not going to be taxable.

Christina Care: Right. That’s a little grey area.

Alan Lean: The caveat to that very general statement, so I think in every individual case you’d need to look at it very carefully.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: I’m glad you’re here Alan, I would not have had a clue.

Christina Care: It was just an interesting question, I thought. I wonder what your opinion would be of this. Someone’s asked, should agents take a cut from a minimum wage job? What do you think?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Well, I mean, it’s what you have agreed with your agent that would define what they can take and what they cannot take. It would be maybe an ethical decision.

Christina Care: It is a slightly more ethical question.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: A question of ethics on behalf of agents. I’m not too sure if ethics and agents… Shouldn’t say much more, but it really, I mean, I think people do need to be very clear on the terms in which they engage an agent to work for them. And I think it’s perfectly legitimate for an artist to suggest to an agent that, but it depends very much on the relationship that they have. And yeah, I’ve seen contracts, I think where an agent would probably waive that or be prepared to. But it’s very much dependent on what’s been agreed to. And yes, if they’re just getting the basic, I mean, I guess the agent would argue that, “Well, hang on a minute, I found the work for you.”

Christina Care: I still got the work. Yeah.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: “You wouldn’t have got that job. You wouldn’t be getting anything if it wasn’t for me doing this. So we deserve something surely”, but maybe reduce the commission or something.

Christina Care: Yeah. So it’s a case by case basis, really.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Everything’s negotiable.

Christina Care: Yeah.

Alan Lean: Yeah. And there’s usually a agent contract, isn’t there, that you sign at the beginning so-

Stephen Duncan-Rice: You should see something in writing from an agent. A lot of people don’t, a lot of people are so happy, so relieved to get some kind of representation, they don’t ask questions. And we always say, get something in writing. Get the agreement in writing. If you’re engaging someone to work for you, you sort of want to know the terms in which you’re working with.

Christina Care: Yeah, of course. The other agent-related question we had was about when to ask for a recall fee and we were talking before we were recording about this, and I was very surprised to know that you actually can ask for a recall fee.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It’s not such a fee on the recall. What it is is basically, if the show… this is in live performance, I’m not as definite on recorded media, I don’t know if they exist in there, but there was in recent years, there have been an obscene number of recalls on some shows. There were some West End musicals where you might be seen 19 times.

Christina Care: Yeah. We’ve heard that a few times.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: So, our members were coming to us saying, “This is ridiculous. It’s costing us a lot to do this. It’s absurd.” And it is absurd. So what the organisers in their sectors, so basically if a producer, if the show is under a UK theatre member or a Society of London Theatre member, on the third audition you can claim travel. And you just get your agent to request from the – I think it would be the…

Christina Care: Casting director.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. Or possibly from the producer’s end, but the agent would contact on your behalf. So you don’t have to ask the question in the audition yourself, which I think people feel very vulnerable about having to ask for money when you’re also going for a job.

Christina Care: Of course. Yeah.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It’s kind of awkward. It’s awkward. So you can do this remote. You can do it via email. It’s just fill in a form, put in your claim, your receipts, and it’ll get processed. And it’s just to cover the travel. It’s from the third one and those are under UK Theatre Equity agreements and Society of London Theatre members. So producers can be members of these professional associations and they’ve made a commitment to the union to abide by these rules. So it’s always worth investigating that and coming to us if you’re not sure.

Christina Care: I have a slightly more fun question, which is, is there anything surprising that you can deduct from your taxes?

Alan Lean: Surprising things.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Haircuts. Can you do haircuts?

Alan Lean: Yeah. Well, it used to be easier. I mean, they’ve got a bit more restrictive with hair as well, so I’m afraid. So to be on the safe side, a lot of accountants put through half. If you’re maintaining a particular style for performance or auditions, that kind of thing. Really, I suppose what the rule is, it’s got to be wholly and exclusively for business purposes. So provided you can prove that, you could bring some quite surprising things under that heading.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: We’re a very diverse union. You’ll be called a performer and be paid professionally, then yeah, there’s all sorts of things could be claimed.

Alan Lean: Yeah. I’m just trying to think. For people who make sand sculptures, presumably, they’ve got some interesting expenses.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Oh, crikey. I didn’t even know we represent them.

Alan Lean: All righty.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: We might do.

Alan Lean: Right. I think we’ve got a few. I’m sure we’ve had inquiries from them before.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: If they’re doing with an audience and getting paid for it. Yeah. Yeah.

Alan Lean: Yeah. Anyway, yes.

Christina Care: Long story short, it could be quite a grey area.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: It could be literally anything.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Literally anything. If you need it to do the job that you’re doing and it’s performance then, yeah.

Alan Lean: One has sprung to mind while we’ve been talking actually and that was one where I had some interesting discussions with a colleague about whether it was allowable. And that was someone who was doing a Santa in a shopping centre who was a member. And it was a shopping centre where they’d had some difficulties recently, some violence, and he was a bit worried about personal safety.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: I remember this.

Alan Lean: So, he bought a bulletproof vest.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Was it stab-proof?

Alan Lean: Stab-proof vest.

Christina Care: Oh my goodness.

Alan Lean: To wear under his Santa outfit and I was thinking, “Actually, God no, he can’t. Surely not.” But when you think about it, why is he getting it?

Christina Care: So he can do his job.

Alan Lean: So he can do his job as Santa.

Christina Care: Safely.

Alan Lean: He’s probably arguably got a reasonable fear that he might be attacked because of what’s been going on there, so having discussed it with a colleague, we decided, go ahead. Yeah.

Christina Care: Oh, quite an extreme one, but possible.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: With a damning indictment of the festive season.

Christina Care: Wow.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Wow.

Alan Lean: So that would be initially surprising-

Christina Care: There you go. Bullet-proof, well sorry, stab-proof vest.

Alan Lean: Stab-proof vest as Santa Claus.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Things went that bad, yeah.

Christina Care: Oh goodness. I think there’s other questions about contracts for that one, but anyway.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Health and safety.

Christina Care: Health and safety.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Very important.

Christina Care: Thank you so much guys for joining me. I only have one more question for you, which is, if things do go wrong, if something seems to be not quite right with, I don’t know, your contract or your situation at work, what should people do?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Talk to us. You can message, go via Twitter, Facebook, email, phone us. We try and make ourselves as accessible as possible. Don’t stay silent on it. Get a hold of us and there are innumerable ways which you can do so. Or sometimes people just want to contact us just so that someone will listen to them, and we’re very happy just to listen.

Christina Care: As well.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. We’ll give you a take on the situation. We don’t have a financial interest in you taking work or not taking work. We just want to make sure that you’re going to be okay in the work that you’re going to do. So there’s no judgement, we just listen, and then we’ll do our best to advise you.

We can’t always fix things. We cannot always provide that silver bullet, magic remedy. Sometimes a bad job is just a bad job and you’ve agreed to do it and it sucks and you just want to get out, fair enough. We’ll do our best to try and help you.

Christina Care: But it’s a good idea to contact you sooner rather than later.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Yeah. Don’t be afraid to either.

Alan Lean: And the same applies for our area, the area I work in. Basically, you’ve got a month roughly to challenge decisions on tax or benefits actually, benefits entitlements. So don’t delay. If you come to us a year into an inquiry, it’s so much more difficult to unscramble it.

Christina Care: Yes. For sure.

Alan Lean: So that’s really important.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Oh, I should also say as a recruitment organiser, if you’re not a member, you should probably join, because otherwise we can’t help you at all.

Alan Lean: Good point.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Which is really the key to a lot of this, it’s like, if you’re not a member, we won’t help because we’re not a charity. We’re a trade union and we’re there to represent the interests of our members at work.

Christina Care: So join your union?

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Indeed. Thank you.

Christina Care: Indeed. Thank you both so much for joining me.

Stephen Duncan-Rice: Thank you for having us. Thank you for inviting us.

Alan Lean: Yeah. Yeah.

Christina Care: Thanks for listening to this episode of The Spotlight Podcast. That’s all for now from the home of casting. If you’ve got any other questions on anything that we’ve discussed today or for any future podcasts, drop us an email at questions@spotlight.com.

We have more information on being self-employed and on all the legal and financial things you should know as a performer. If you have any other questions, send us an email at questions@spotlight.com.

Recorded in July 2019.