Vanessa Alexander talks to us about her career journey to becoming a director, producer and award-winning writer.

Vanessa Alexander defies categorisation. An award-winning writer, director, and producer, Alexander has worked on projects as wide-ranging as Power Rangers, Love Child, The Great, and Vikings: Valhalla.

Her citizenship status follows suit. Born in New York to a New Zealand father and an English mother, Alexander now resides in Newcastle, Australia after stints in Paris and the UK. Add to this five children, one foster son, two ex-husbands, and a mid-life crisis at clown school, then it’s clear to see why Alexander is “rarely short of inspiration.”

What initially sparked your love of the arts?

I grew up in a family where there was a lot of science, but my father actually played the piano really well. His mum had played the piano in movie houses. My father loved taking us to musicals and plays – I don’t know what his master plan was, to take us to all those and then imagine that we would want to be doctors!

My mum taught me to read when I was really young. When I was six, I went to school and was [moved] up two years, so I graduated from high school when I was 15. I was a super good reader and spent my whole childhood reading, so I always thought I was going to be a novelist.

Your career has been tremendously varied – writing, directing, producing – was this always the plan?

No, there’s no plan. I feel like life is really hard if you’re a woman because it’s a lot to juggle the expectations on you, as a mother and the expectations on you at work. I don’t know if it’s true now, but in my generation, you had to be 50 times better than every man… My joke [is] as a woman, you’re ‘emerging’ and then you’re dead.

I had an existential crisis after a few seasons of Power Rangers. I used to wake up in the night – I called it ‘the dream of the hundred thousand vaginas’ – where my entire female ancestry would visit me in my sleep and be like, “What are you doing?”

So I went to Paris, taught at the International Film School, and studied with Philippe Gaulier – the French clown who trained Sacha Baron Cohen. At the end of that year, we moved back to Australia and I was essentially starting my career again in another country at 42.

I could not get work in Australia. I could not get work, straight up. Eventually, I abandoned directing and decided to return to writing. I ended up in the UK for my ex-husband’s sabbatical, so I had to give up all my Australian work. I used the time there to get an agent and went through an entire year of meeting, meeting, meeting. Never got any work.

I came back to Australia, separated from my husband, and had no work because I’d given it all up for the sabbatical. So I boarded a flight back to the UK and went into the story room for Tin Star. I’ve done a lot of writer’s rooms [since] and it was a very prescient thought because once I started doing them, I got a lot of work.

On the topic of writer’s rooms, how do you approach being the lead writer?

If you’re the lead writer, usually you write the pilot, or the series is your idea, or you’re commissioned to take an original piece of IP [intellectual property] and find the television-relevant take. I do that, but I actually also like not doing that. I’ve learnt a lot by being a ‘right-hand man’ for other people or working in their writer’s room. Everybody brings their own weird strengths to the writer’s room, but in the end, as the lead writer, it’s your problem to solve.

How involved have you been in the casting process?

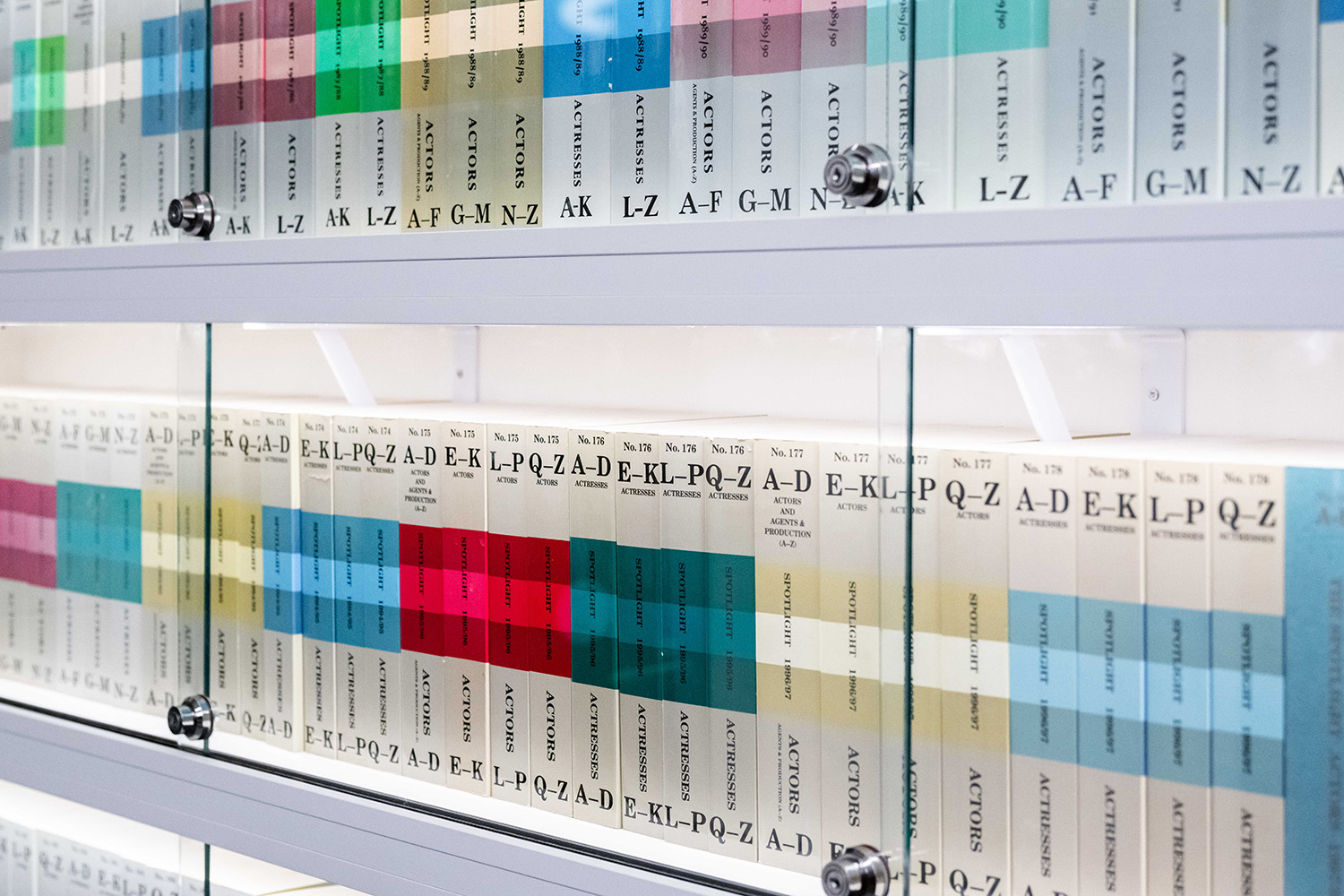

For the first 10 years of my career, I always directed or produced things I wrote – sometimes all three – so I was always involved. In something like Vikings or The Great, you can suggest people, but ultimately it’s the lead writer and producer’s decision.

With Vikings, Jeb [Stuart] shared the final auditions with us. Obviously, it’s nice to be able to say what you think, but it’s primarily helpful as a writer because you go, “Oh, I hadn’t seen that in that character”. Actors bring their own stuff, right? So eventually it becomes writing for the actor. [For example], I found it really helpful to see Emma [played by Laura Berlin]. I found that character weirdly hard to write. Then once I saw her audition, I was like, “Ah!” It just makes it easier to write.

Do you notice common threads when you reflect on the actors you’ve most enjoyed working with?

My favourite actor I’ve ever worked with is Robyn Malcolm, a New Zealand actress. I love her. She’s got so much warmth and naughtiness and spark, and she can bring that to really diverse characters that don’t all feel the same. I think something special that those actors have, is this thing – it’s like they’re carrying an energy where you want to watch them.

I’ve got a lot of respect for actors. It’s a hard job. And mostly, I think actors are very generous with each other. Good actors give each other a lot.

Given the journey you’ve had, what does ‘success’ mean to you today?

When I was younger, I thought about whether I was successful or not, whether this hadn’t worked out because I wasn’t good enough. What I’ve come to see is that it’s actually a crap way of thinking.

A lot of female writers ask me, “How do you deal with imposter syndrome?” And I think imposter syndrome is a sign you’re thinking too self-centred. You’re really thinking about yourself and your own insecurities. You have a duty to all the women who have gone before you, to improve women in other people’s stories, or to take up that space and open the window for the next person behind you.

It’s not about how successful you are, it’s [about] should this story be told? What stories haven’t been told? What stories need to be told? It’s really an act of duty.

Your career alone is astounding, but it’s made all the more impressive by the fact you’re a mother of six. Do you have any strategies that make this possible?

I should write a book! This is my number one piece of advice: be average. In their teenage years, they’re going to hate you anyway. Women are way too hard on themselves.

The other [tip] is bags. You need bags. Not just school bags – you need music bags, swimming bags, soccer bags. They’ve got to be different colours, and you put them up on hooks, and everything goes back in the bag. You’ll reacquire five hours a week!

Thanks for your time Vanessa. We have tips for writing your own work on our website and plenty more inspirational interviews with industry professionals if you’d like to read more.

Tahlia Norrish is an Aussie-Brit actor, writer, and current MPhil Candidate at the University of Queensland’s School of Sport Sciences. After graduating from The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts (Distinction, Acting and Musical Theatre) and Rose Bruford College (First Class Hons, Acting), Tahlia founded The Actor’s Dojo — a pioneering coaching program centred on actor peak performance and holistic wellbeing.

Tahlia Norrish is an Aussie-Brit actor, writer, and current MPhil Candidate at the University of Queensland’s School of Sport Sciences. After graduating from The Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts (Distinction, Acting and Musical Theatre) and Rose Bruford College (First Class Hons, Acting), Tahlia founded The Actor’s Dojo — a pioneering coaching program centred on actor peak performance and holistic wellbeing.

Headshot credit: Ben Wilkin