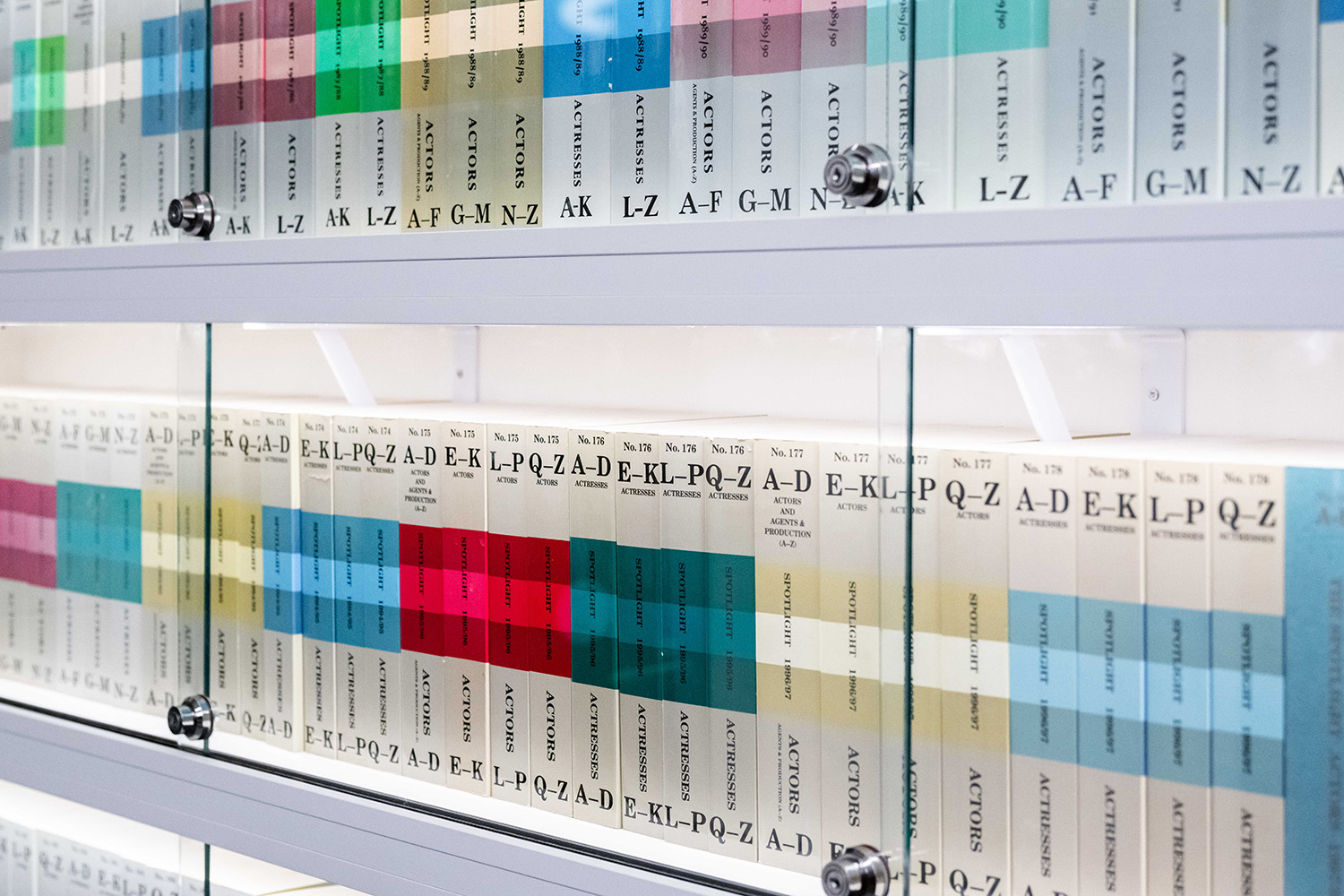

Paines Plough’s Joint Artistic Director James Grieve talks to Spotlight about moving from acting to directing – and how important it is to make your own work!

James Grieve is the Joint Artistic Director of Paines Plough (“PP”) alongside George Perrin. He started out as an actor before moving over to directing, and as a result, James had a lot of great advice to share with Spotlight for those looking to direct their own work and take it to the Fringe – or indeed any independent theatre, across the UK. Read our interview and top tips below!

I was seeing a lot of plays that didn’t feel very relevant to me. I would be seeing a lot of Shakespearean productions that didn’t seem to have much to say to me about my life, as a teenager or a person in my early twenties. I was very aware that most of my friends did not think that theatre was for them. Most of my friends were into live music, football and drinking… So, the thought was to create some work that was for my friends, about my friends – the lives that we lived, about our politics, the things we were thinking about, what was troubling us or making us happy. I don’t think I ever lost that impulse.

How did you decide you wanted to be a theatre director?

Like many directors, I realised I wanted to be a director whilst being an actor. I did a few school productions and then when I got to university at Sheffield, I read English – there wasn’t a drama course – but I got involved in their theatre scene and did a couple of shows. I have heard so many stories of other directors that are just the same. It was just one day, standing on stage looking around and realising that everyone was standing in the wrong place, the lighting was rubbish, the costumes weren’t appropriate, and nobody had come because the marketing was so poor. It was that thing of megalomania where you just go: “I don’t want to be standing here, I want to be in control of all the other elements that go into making theatre!” Then I just started directing plays with absolutely no idea of what I was doing. I didn’t have any idea that there might be a professional job like that out there – I didn’t really know there were directors. I just wasn’t cognisant of it in any meaningful way. So, I just started in university and it snowballed from there.

What attracted you to Paines Plough specifically?

Whilst still at university, I started a company to produce work in a different way to [how it was done at] the university, which was one of those brilliant student societies, run democratically, so nothing ever gets done. I wanted a dictatorship! The company was called Nabokov, and George [Joint Artistic Director of PP] ran it with me for 10 years. We came up to Edinburgh, saw PP shows at the Traverse – we were fanboys of the shows we saw and built Nabokov in PP’s image. When we went for the interview for PP itself, we kind of sat down and said, “We’ve been trying to run PP for the last 10 years but on a much smaller scale, so now can we please run PP?!”

I think there was a prevailing thought when I started out that the way you got a career was to try and do some good stuff and then somebody would magically call you up and go, “Please would you come and direct Hamlet?” The finger would come out of the sky and point at you! I don’t really think that happens very much anymore. It certainly didn’t for me. I don’t think anyone should sit around waiting for something to happen.

What is your approach to new writing – what would you say is the role of the writer at PP?

We have an ideology that the playwright is the lead creative artist in everything that we do. That guides all the decisions that we make as a company. It comes down to placing the writer at the centre of the organisation. Sometimes writers have a show and feel like it’s all in the building but they are not really allowed in – they are called upon only when there’s a line that needs rewriting. But we see a writer’s role in the whole process very differently. For example, when Jack [Heaton, Marketing Manager] is evolving the marketing around a show, the writer will be consulted every step of the way. We don’t unilaterally come up with the marketing campaign. We represent your play in the best way, and you help us understand how you want your play to work, etc. We have the writers in rehearsals all the time, we want writers in tech, talking to the actors, designers, directors, etc. about the creative gesture of the play. We’re not alone in that ideology but it is absolutely our guiding principle and I think that is distinct about PP.

What is it that attracts you personally to a new script?

One of the initial impulses for me about making theatre was that I was seeing a lot of plays that didn’t feel very relevant to me. I would be seeing a lot of Shakespearean productions that didn’t seem to have much to say to me about my life, as a teenager or a person in my early twenties. I was very aware that most of my friends did not think that theatre was for them. Most of my friends were into live music, football and drinking. Then you go to the theatre and you see a costume drama and you think, “Yeah, if I brought my friends, they would never ever come again.” So, the thought was to create some work that was for my friends, about my friends – the lives that we lived, about our politics, the things we were thinking about, what was troubling us or making us happy. I don’t think I ever lost that impulse. It’s still pretty much the same today, though the themes of the work have perhaps changed as I’ve gotten older! I still feel that we talk about how we can make work that confounds people’s expectations of what theatre is. And this speaks directly to what is happening today in the world. Of course, you can revive classics to speak to a new generation, but I think there’s something very exciting and alive about sitting down with a playwright and saying, “We can put this on in 6 months or a year’s time. What is the most important thing we’ve got to say?”

I find myself watching Edinburgh shows now and again where the story doesn’t kick in until the 40-minute mark – it’s too late by then!

How do you discover writers, and what is the PP process of developing a production?

One of the big reasons why the whole of PP is up in Edinburgh for the month of August is because this is such an amazing place to discover new writers. Every Edinburgh Fringe, we come away having seen hundreds of shows between us, each with a handful of names that we think are really exciting. We’ll then follow their careers, try and see as much of their work as possible, and start a relationship with them that might just be a coffee when we’re in Edinburgh, or maybe we’ll tell them to come and see us in 6 months’ time. That relationship deepens, we try and hang out with them a bit more, understand their taste, until we decide it’s a good match between them and PP.

I suppose something that’s distinct about PP is that we commission to production. Most theatres will commission 10 plays and put on 2. We say to the writer that we commission that we will absolutely put their play on, because we want to put on whatever they write – they’re a writer that we love. It gives it a different energy, that is like, okay, we are going to Edinburgh, here’s your first deadline, don’t miss it! That can be terrifying for writers, but they also come back regularly and feel it’s really exciting – you’re forced into an immediacy with your writing. By doing that we get work with a certain energy to it and it feels very alive – it has only just been written.

I’d really encourage people to just take the plunge and find some nice people to work with. Make some work and just put it on. Don’t have any end game to that work – don’t think, “I need a review,” or “I need to sell loads of tickets,” or anything like that, other than, “I’m just going to make my work, get some people to come and see it even if I know all of them, just to see if I can do it.” The sense of satisfaction, artistic merit and reward, is amazing.

Do you have any advice for writers regarding what makes a good show for the Fringe specifically?

In our format, I think it’s just story, story, story! I find myself watching Edinburgh shows now and again where the story doesn’t kick in until the 40-minute mark – it’s too late by then! It can’t be a 40-minute build-up for a 20-minute pay-off. I think in Edinburgh there’s so much on offer and everyone’s so busy, if you’re going to ask somebody to spend an hour with your story, make sure it’s a really good story.

Any advice for the theatre-makers out there who have perhaps taken their first show to the Fringe, and are wondering what to do next?

Do another one. Do it again. No matter how your show goes in Edinburgh. First thing is you made a show. It puts you in the top couple of percent of people – you’ve done something amazing. So even if it hasn’t gone how you wanted it to go, you still have to look at yourself in the mirror and go, “I’ve done something really useful, important, productive and creative with my life. I’ve made something.” And then after the Fringe, everybody needs a lie down in a dark room. So, September is never a good time to make decisions about your life or career. Everybody leaves Edinburgh going, “I’m never going back!” Have September off, be nice to yourself, eat good food, see your non-theatre friends, and then in October just check in and see if you want to do it all over again.

I’ve always gotten to October and gone, yep, I want to do it all over again. And if you go, “Nope, I don’t really fancy putting myself through that again,” then that’s absolutely fine. If you’ve got the itch, then start again. And of course, Edinburgh is not the only Fringe – there are plenty of other places and spaces available. There’s a lot of doom and gloom about new writing in big theatres, but on a smaller scale, new writing is as strong as it has been in a generation. We’re touring our new plays to over 60 small scale venues every year, and people are really passionate and exciting at those venues. Even if Edinburgh hasn’t been all that people dreamed about, there’s a lot else – it doesn’t end at the Fringe!

Top Directing Tips from James

1. Make your own luck

My big advice would be ‘do it!’ It’s a very different industry to the one I joined 20 years ago, far more competitive. There are far more people in it, particularly actors. I think there was a prevailing thought when I started out that the way you got a career was to try and do some good stuff and then somebody would magically call you up and go, “Please would you come and direct Hamlet?” The finger would come out of the sky and point at you! I don’t really think that happens very much anymore. It certainly didn’t for me. I don’t think anyone should sit around waiting for something to happen.

2. Be prepared to get stuck into small-scale productions

If you’re an actor, that can be a difficult cycle with auditions, not getting them, etc. I think the more people who can take ownership over their careers, the better. Having produced my own work for 10 years at Nabokov, I found that so rewarding and exciting, and I am now able to pay the rent consistently by doing the thing that I love the most, which is directing plays. But I am only here because I scrabbled around and got actors to do plays with me in tiny theatres above pubs for years and years.

3. Do it without expectations!

I’d really encourage people to just take the plunge and find some nice people to work with. Make some work and just put it on. Don’t have any end game to that work – don’t think, “I need a review,” or “I need to sell loads of tickets,” or anything like that, other than, “I’m just going to make my work, get some people to come and see it even if I know all of them, just to see if I can do it.” The sense of satisfaction, artistic merit and reward, is amazing. We’re increasingly in a world where self-producing is the way forward, it’s absolutely necessary. It’s a gig economy.

4. If you can’t pay, be sure to take care of your team

I find this very complicated, because ideologically I believe everybody should be paid. However, I can’t get away from the fact that that wasn’t the case when I was starting out. I didn’t get paid personally for about 5 years. When I got paid for the first time when Nabokov got an Arts council fund in 2004, I paid myself a wage from it and it felt both miraculous and almost fraudulent! Before that everybody worked for free. I think there’s something very important about treating everybody properly. If you can’t pay people, I think it’s really important to have a verbal contract within which everybody understands what is going to be asked of them and everyone mutually agrees that they want to be a part of it. If you look after people properly, they’ve got a bottle of water in rehearsals, you can buy them a pint at the end of the day or buy them some lunch – just make them feel good about themselves for a day, take care of them.

5. Don’t be deterred by the big theatres

Small independent theatre companies are taking more and more power from the big theatres. The future will look very different. There is an opportunity for anybody who wants to just make work to go out and make it. Use technology, use whatever you can imagine to make work in an interesting way. Go for it!

Thanks to James for giving us his time. Catch the variety of excellent PP shows on in Edinburgh this week at the Roundabout at Summerhall, or when the shows tour across the country over the next few months! Dates and locations can be found online here.

Image credits: Jonathan Keenan and Matt Humphrey