Tips for Shakespearean acting from breaking down Shakespeare’s verse to acting techniques.

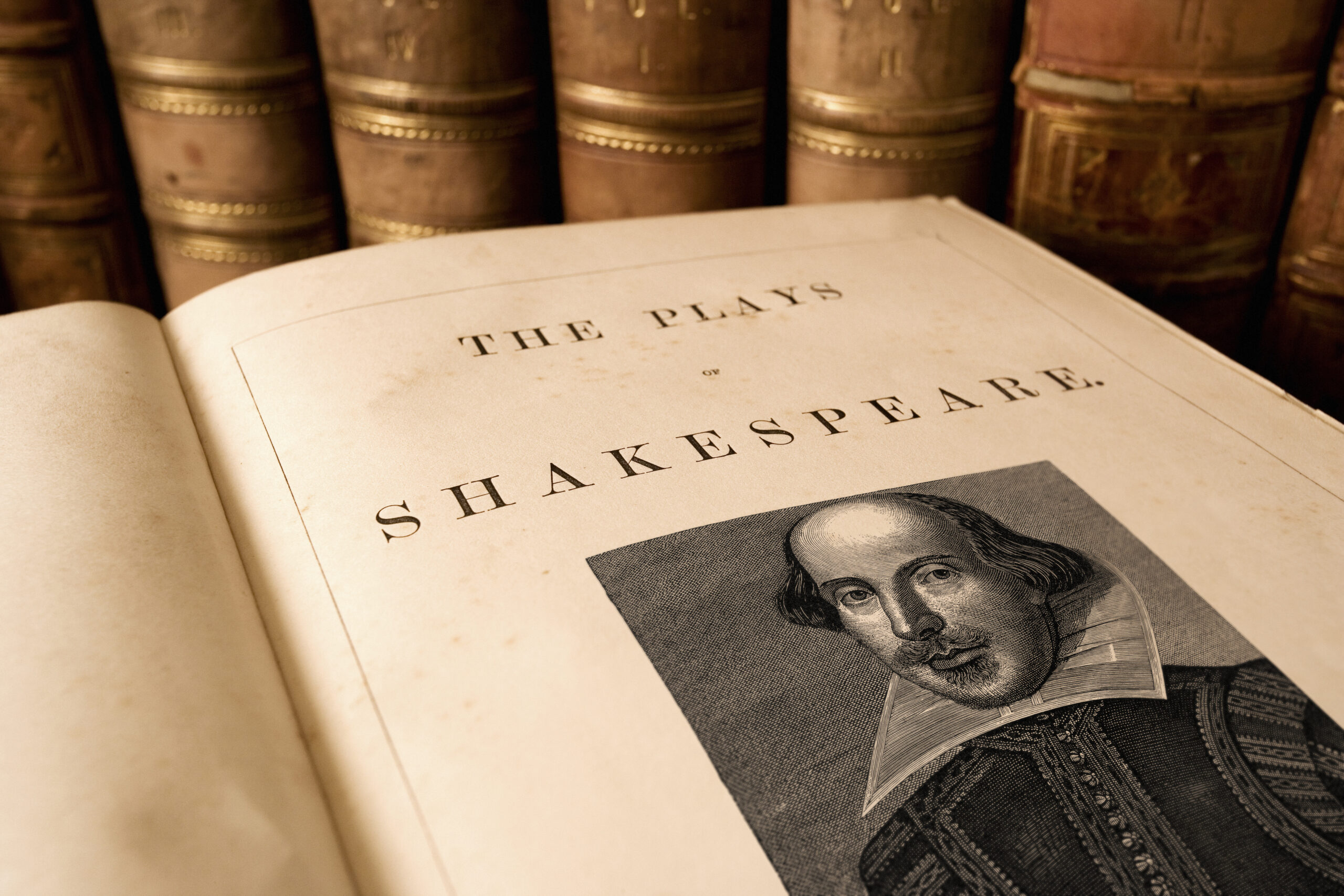

For over 400 years, Shakespeare’s plays have allowed actors the opportunity to play out the greatest heights of tragedy and explore the joy of outlandish comedy.

One of his most popular plays, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, has been staged over 118 times. Others, like Romeo & Juliet have been transported to the screen as films, such as Baz Luhrmann’s reimagining, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes.

Most of us would have first encountered the Bard’s work in GCSE English – probably Macbeth, which is one of the most commonly used plays for exams. However research shows students struggle to understand Shakespeare’s work because of the complexity of the language. They find it difficult to relate to, so fail to see the relevance of material that was written during the 16th and 17th centuries.

As an actor you might be familiar with some of these issues when approaching Shakespeare’s work for the first time. If you can’t understand what you’re saying, how can you possibly master a good Shakespearean performance?

When I revisited Shakespeare as a drama student, I was encouraged to explore the text in a way that dismantled the preconceptions I had about classical work. Shakespeare didn’t have to be performed in RP and it didn’t need to be set 400 years ago. Shakespeare’s work was ultimately meant for the stage and once you translate the language, you can approach it in the same way you might a modern play.

The Macbeth I studied in GCSE English was not the same Macbeth I revisited as an actor. The language felt less intimidating once I could comprehend what was actually at the heart of Shakespeare’s work, and with a few tips and tricks, you can understand it too.

Auditioning for Shakespeare Productions

When auditioning for Shakespeare productions, you should have at least two monologues available to use. Ideally, a dramatic monologue and a comedic one, to show contrasting styles. Choose a monologue that you know you can memorise, from a play that you’re familiar with.

When auditioning for Shakespeare, you want to showcase that you understand the language and that you can perform with nuance, adding your own interpretation to the role. It’s not necessarily about picking a role that no one else will but adding value to the monologue you’re performing so that you’re clearly presenting your ability in the audition.

You should have your monologue memorised and know it well enough to take direction if needed. Knowing the plot of the play is also essential, you might get asked questions about your character, and understanding the plot of a Shakespeare play will help you show that you have a grasp of the text.

Understanding Shakespeare as an Actor

Before reading Shakespeare’s work, it’s helpful to identify the language and literary devices he uses. Some of the most common struggles for beginners are knowing how to use ‘scansion’ for iambic pentameter, understanding the difference between prose and verse and why some characters only use one or the other.

Here are some of the key factors to understanding Shakespearean language:

Verse and Prose:

Shakespeare wrote in both verse and prose, and an easy way to identify which is which is how the lines take shape on the page. Visually, verse is aligned on the left margin, with a jagged edge on the right. The beginning of each line is capitalised and shorter than prose. The lines are also organised into stanzas with potential breaks, similar to poetry.

Here is an example of verse used in Much Ado About Nothing (Act 4, Scene 1):

FRIAR:

“Your daughter here the princes left for dead.

Let her awhile be secretly kept in,

And publish it that she is dead indeed.”

Most characters that speak in verse are of high status, so most kings, queens and upper-class individuals like ‘Prince Hamlet’ or ‘King Duncan’ in Macbeth use verse. However some characters may switch from verse to prose and vice versa if the occasion calls for it. For instance ‘Beatrice’ in Much Ado About Nothing (Act 3, Scene 1) uses verse for the first time in her soliloquy to directly address the audience.

Prose, on the other hand, is visually aligned in a block shape and goes right to the edge of the page. It’s closest to conversational speech and doesn’t use metric or rhyme.

Prose is significantly used to show a character’s lack of intelligence or low status. For instance, ‘Dogberry’ in Much Ado About Nothing only speaks in prose and uses malapropisms. Higher-status characters may switch to prose in moments of high emotion or to emulate regular speech patterns.

Here is an example of the use of prose from Much Ado About Nothing (Act 3, Scene 5):

DOGBERRY:

“One word sir: our watch, sir, have indeed comprehended two aspicious persons and we would have them examined this morning before your worship.”

Iambic Pentameter

Iambic pentameter is a type of metric used to describe the rhythm established by the words in each line. Iamb is a metrical foot with two syllables, (unstressed followed by stressed) and pentameter means five metrical feet. So a line of Iambic pentameter consists of five Iambs making 10 syllables.

It’s also a stress pattern consisting of stressed and unstressed syllables. The process of analysing the rhythm of verse is known as ‘scansion’ but first you can say the lines aloud to see where the rhythm might fall naturally.

Using Hamlet’s speech below, begin by saying the lines naturally:

HAMLET:

“To be or not to be, that is the question”

To scan the verse, say the lines again – but this time stress the capitalised words:

HAMLET:

“To BE or NOT to BE, that IS the QUESTION”

It helps to clap or tap on the stressed words, so you can establish the rhythm.

To use scansion in your script, you would take a line of verse and mark where the syllables are unstressed and stressed using these symbols:

| — | Stressed syllable |

| ˘ | Unstressed syllable |

| | | A vertical line to identify feet |

| ‖ | A double vertical line for a pause within the line of verse. |

A graphic scan of the line of verse would look like this:

To be | or not | to be | that is | the question

˘ — ˘ — ˘ — ˘ — ˘ —

If you’re struggling to establish the rhythm, scanning the lines in this way or using X’s and /’s will help you read the lines of verse with the stressed and unstressed words clearly marked.

Think of the lines as poetry – there is a rhythm and structure to be performed.

Shakespeare’s Glossary

There are many commonalities between Shakespeare and modern English, however a misconception is that the language is outdated and therefore irrelevant to us. According to Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust, his works actually provide the first recorded use of over 1,700 words we still use today.

The word ‘lonely’, for instance, was first coined in Othello and the word ‘bedazzled’ was first used in The Taming of the Shrew. There are many words in the Shakespearean language that have become extinct in their use outside of classical text which can make it difficult to articulate as an actor.

Words like ‘thou’, ‘thee’ and ‘thine’ can be easier to translate to mean ‘you’, ‘to you’ and ‘yours’. However, archaic words that appear in the text can be looked up in a Shakespearean glossary. Once you identify the meaning of a phrase or word, you can unlock a deeper meaning through its modern counterpart.

Take this line from Coriolanus (Act 3, Scene 3) as an example:

CORIOLANUS:

“You, common cry of curs!”

This phrase can be translated to mean “You worthless pack/crowd of dogs!” It’s an insult and during the speech, ‘Coriolanus’ is scolding the people who have rejected him. The rest of the speech builds on this and indicates his emotional state.

If you take the phrase and say it in your own words it can help realise the emotional state of your character. You can then return to the original text with a deeper understanding of what you’re saying and how you should be feeling.

The language Shakespeare uses is intentional, so take the time to find out what he’s trying to convey to aid in your performance as an actor.

Categories and Themes in Shakespeare’s Plays

Most of Shakespeare’s plays can be grouped into four categories: tragedy, comedy, history and the problem plays. Identifying the category is the first step to understanding the themes Shakespeare depicts in the events that unfold.

- Most of his tragic plays, like Titus Andronicus and King Lear, depict a sombre nature and most likely end with one or more characters dying on stage.

- Comedic plays like, Love’s Labour’s Lost and As You Like It, depict lighter themes with funny plot twists and usually end with a wedding or celebration.

- The histories are set in medieval England – think King John, Richard III and Henry IV. Although they’re not historically accurate, they use historical events as a base to explore class systems and the social prejudices of the time.

- The problem plays are simply plays that don’t fit neatly into any of the categories: All’s Well That Ends Well, Measure for Measure and Troilus & Cressida.

Some of Shakespeare’s plays might cross over into one or more categories, such as The Merchant of Venice. While it’s classified in the first folio as a comedy, it depicts tragic themes and explores a romantic plot line with the characters ‘Portia’, ‘Bassanio’ and the caskets.

Identifying the themes explored within the categories can help you improve your performance. For example, in a tragedy where there’s the prospect of impending death, your character would carry a serious demeanour, echoing a tragic fate. In a comedy, exploring themes of love and confusion with a hilarious misunderstanding to rectify, knowing your character has a happy ending will allow you to lean into making choices that will reflect the themes.

Imagine if the character of ‘Hamlet’ were to appear in A Midsummer Night’s Dream? Give the appropriate weight to the fate of the character by identifying Shakespeare’s themes and categories.

A Play in Five Acts

Each of Shakespeare’s plays can be divided into five acts. When you read the play, you can denote where your character is in their journey depending on the act. You can also anticipate the level of action your character might go through in the story, depending on when and where they appear.

- The first act introduces the setting, and the players and lays out the main conflict.

- The second act is where the action starts and you begin to see the conflict unfold.

- The third act reaches a climax.

- In the fourth act, the action begins to resolve, with the main conflict coming to a head.

- The fifth act is the resolution and depending on which of the categories a play falls into, this can mean a happy ending or a tragic one.

The Shakespearean Accent

A preconceived notion about performing in Shakespearean plays is that you have to use a pronunciation dialect. This is largely due to the belief that the elevated language requires a ‘posh’ sounding accent.

However, Shakespeare himself was from Stratford-Upon-Avon in Warwickshire, and although there are no known recordings of how he might have sounded, scholars believed he might have spoken with a Midlands dialect.

Trying to grasp Shakespearean text with an accent that’s incredibly different from your own only perpetuates the stereotype that classical plays aren’t for the working class. I was born in Birmingham, so for a West Midlands-based production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I spoke in my own accent. However, in a production of As You Like It set in 1960s America, and a production of Julius Caesar set in 2016 centred around US politics I used an American accent.

Breaking down the stereotypes about classical work being inaccessible starts with uplifting actors from under-represented communities.

While it may feel like a gargantuan task to use scansion and consult a glossary for extinct words, what’s beneath the homework makes his work relevant to you and will enrich your performance.

If Shakespeare has been performed for the last 400 years, it’s likely to be performed for the next 400 years as well, so make your interpretation of the Bard’s work mean something. It’s not about mastering classical text to ‘get it right’, it’s about finding the connection from the character to the actor, and the actor to the audience.

Useful Resources:

- Spark Notes

- Reduced Shakespeare Company

- Shakespeare glossary

- RSC Shakespeare’s Language

- The Complete Works of Shakespeare

- Monologues for Shakespeare